The Deep Roots of Chinese Cooking in Thai Cuisine

Discover how Chinese cooking has shaped the gastronomic evolution of Thai cuisine!

Discover the authentic in Asian cuisine food

Umami has, like so many great and ambiguous words, a variety of translations. Taken from Japanese, it’s been defined as yummy, deliciousness or a pleasant savoury taste, and was coined in 1908 by a chemist at Tokyo University called Kikunae Ikeda. Ikeda had noticed a certain depth of flavour in asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat, but most intensely in dashi – that rich stock made from kombu (kelp) which is widely used as a flavour base in Japanese cooking. So to get to the bottom of this gastronomical mystery, the flavour chemist studied kombu, eventually pinpointing glutamate, an amino acid, as the source of savoury wonder. He then learned how to produce it in industrial quantities and patented the notorious flavour enhancer MSG.

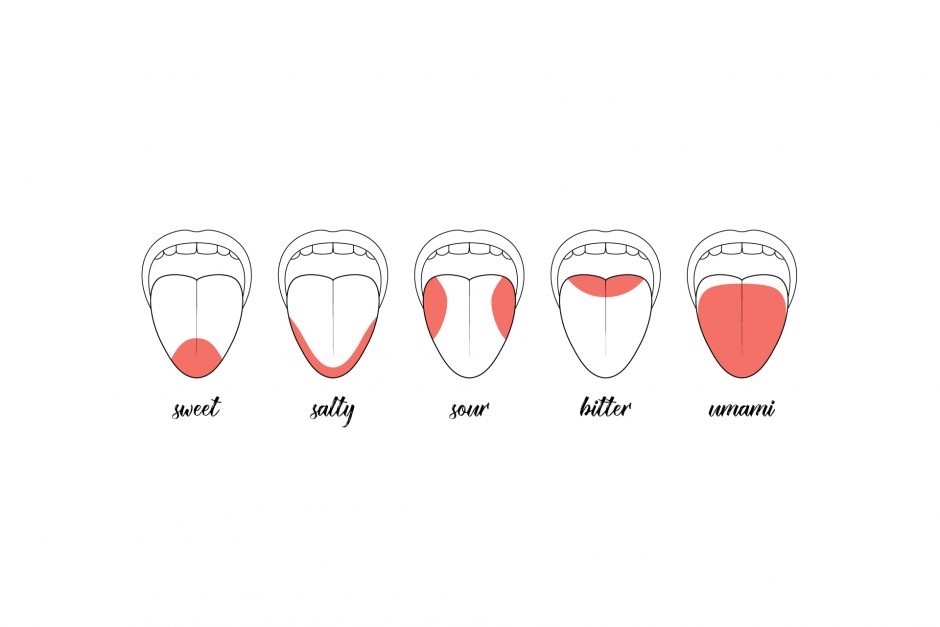

Despite being officially discovered in 1908, umami has only recently been recognised by western scientists. The “fifth taste”, after salt, sweet, sour and bitter – is a fascinating piece in the jigsaw of our gastronomic evolution. Recent studies officially confirmed that our mouths contain taste umami taste receptors, so all the theorizing by chefs down the years was justified. Umami is why the Romans loved liquamen, the fermented anchovy sauce that they sloshed as liberally as we do ketchup today. It is key to the bone-warming joy of gravy made from good stock, meat juices and caramelised meat and veg. It is why vegemite is loved all over Australia, and it’s responsible for the surge in popularity of pho, ramen and hot pot.

Paul Breslin of Monell University, who was among the first scientists to prove the existence of umami taste receptors, told that Guardian umami is most prevalent in “Something that has been slow-cooked for a long time.” Raw meat, he points out, isn’t that umami. You need to release the amino acids by cooking, or “hanging it until it is a little desiccated, maybe even molded slightly, like a very good, expensive steak”.

Fermentation also frees the umami – soy sauce, cheese, cured meats have it in spades. In the vegetable kingdom, mushrooms are high in glutamate, which explains why they’re often described as meaty. It’s one of the reasons bone broth is so moreish. The slow hours of simmering release all the glutamate you can possibly hope for, and make noodle soups so delicious.

The great thing about umami is how it stacks. Glutamates occur naturally in a number of foods, so when you add them together, like meaty ragout and parmesan cheese, or a cheeseburger with ketchup, you get an umami flavour bomb. The ingredients enhance one another so the dish packs more flavour points than the sum of its parts, and you’re left craving more.

So why do humans love it so much? Advertisement.

Well, just as humans evolved to crave sweetness for sugars (sugars = calories which = energy), and avoid bitter tastes (often represented by toxins), umami represent protein to the body. Protein is made up of amino acids, the building blocks of life. So why is it present in cooked foods and not raw? Breslin’s answer is that cooking or preserving our main protein sources detoxifies them. “”Part of the great digestion formula,” he says to the Guardian, “is not only the ability to procure nutrients, but it’s to protect yourself from getting sick while you do that. If you don’t get proper nutrition you can live to see another day, but if you’re poisoned, it can end it for you right there.” But the bigger question is why are some vegetables that are low in protein high in glutamate? Some cases, such as mushrooms, says Breslin, we cannot explain. However, for others, such as tomatoes, it could be the same reason why fruit is so sweet. “The sugar is there so you grab the fruit and spread the seeds around. It could be that the mixture of sugar and glutamate in some of these foods is there to make them extra attractive.”

Umami is prevalent in many Asian cuisines. Apart from the noodle soups we’ve already mentioned. One delicious sauce of umami is oyster sauce. Traditionally made from slow simmering oysters for hours till they break down into a thick brown sauce, it might be the perfect example of how produce umami. Slow cooking a protein for hours to release all that delicious glutamate.

Give it a go if you’re really craving a savoury umami hit.

Discover how Chinese cooking has shaped the gastronomic evolution of Thai cuisine!

Crispy outside, savoury and tender within, these noodle-wrap prawns are sure to delight!

-300x200.jpg)

Enjoy the rosy layers of sweet Kuih Lapis with our step-by-step recipe!